"Smallpox Comes to Boston"

On this pub date of our new book, we share an excerpt about the smallpox outbreak in Boston in 1721 and the inoculation campaign spearheaded by the Reverend Cotton Mather.

Author’s Note: The following is an excerpt from Chapter 2: Smallpox Comes to Boston, in our new book (published today) Vaccines: Mythology, Ideology, and Reality.

Cotton Mather was, along with his father Increase Mather, co-pastor of the Congregationalist Old North Meeting House in Boston, where he continued to preach the Puritan theology of his forefathers. A child prodigy, he attended Harvard at age eleven and remains the youngest student in the college’s history. Like Newton, Mather perceived the world to be comprised of two realms—the supernatural and the natural—and he saw no contradiction between these worlds. On the one hand, he was a strong supporter of empirical, experimental science. On the other hand, he believed in the existence of devils and witches who could exert their power in the world and do evil. During the Salem Witch Trials, he served as a consultant to the presiding judges and defended his view of the matter in his 1693 book Wonders of the Invisible World.

The trials were unique in the history of American jurisprudence because the court admitted so-called “spectral evidence”—that is, testimony of a witness who claimed that the accused appeared to her and harmed her in a dream or a vision. The proceedings got especially spooky when some witnesses cried out as though they were being tormented while the accused were questioned. When asked for his opinion of spectral evidence, Mather pointed out that it could be proper evidence, but he cautioned that the Devil could also assume the image of an innocent person.

During the witch trials, witnesses seemed to be suffering from invisible causes, and they claimed they were being tormented by apparitions that only they could see. Were the witnesses pretending, suffering from intoxication or illness, or really being tormented by witches doing the Devil’s work? The judges concluded that, of the two hundred accused, twenty had indeed practiced witchcraft on the witnesses. They drew this conclusion with no reliable means of knowing whether it was indeed the cause. We now look back on the Witch Trials and marvel at the superstition of people at the end of the 17th century. However, when confronted with a pathology whose cause is invisible, it is natural and rational for people to speculate about the cause and its cure, even if they have no reliable means of knowing it.

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, Cotton Mather seems to have turned his attention increasingly to natural science and submitted multiple papers to the Royal Society in London, which made him a fellow in 1713. That fall, a virulent measles outbreak hit Boston and killed his wife, three of his children, and his maidservant. His diary entries about his terrible trial are heartbreaking to read.

November 9, “Between three and four in the Afternoon, my dear, dear, dear Friend [wife] expired.”

November 14, “The two Newborns, are languishing in the Arms of Death...”

November 15, “... my little Jerusha. The dear little Creature lies in dying Circumstances.”

November 18, “About Midnight, little Eleazar died.” November 20, “Little Martha died, about ten a clock, A.M.”

November 21, “...Betwixt 9 h. and 10 h. at night, my lovely Jerusha Expired. She was 2 years, and about 7 months old. Just before she died, she asked me to pray with her; which I did... Lord I am oppressed; undertake for me!”

November 23, “...My poor Family is now left without any Infant in it, or any under seven Years of Age...”

Why exactly the Boston measles epidemic of November 1713 was so virulent is not understood, though it’s likely the New England colonial settlers did not have the same level of herd immunity against measles that prevailed in Britain and Europe at the time. In his October 30 diary entry, Mather wrote that the disease was much worse “in families where they conflict with poverty.” While Mather was relatively affluent, one wonders if, that autumn, Boston was poorly provisioned with foods containing Vitamin A, whose deficiency is strongly associated with severe measles illness.

Mather’s devastating loss intensified his interest in disease and how to treat it. His 1714 letter to the Society, confirming his favorable opinion of smallpox inoculation, was characteristic of his avid curiosity about nature and medicine at this time. Seven years later, in 1721, he was presented with the unhappy opportunity of putting the theory of variolation into practice when the British passenger ship HMS Seahorse arrived in Boston from Barbados with a crew of sailors infected with smallpox and transmitted it to other sailors in the harbor. On May 26, 1721, Mather noted in his diary, “The grievous calamity of the small pox has now entered the town.”

Mather and a Harvard physician named Zabdiel Boylston advocated inoculating the town’s population with inoculum taken from the relatively small number who were already infected. Using a needle dipped into a smallpox pustule, Boylston inoculated his six-year-old son, his thirty-six- year-old slave, and the slave’s two-year-old son. All experienced relatively mild cases of smallpox without disability or disfigurement. In November, Boylston inoculated thirteen students (including Mather’s son Samuel) and two faculty members at Harvard, all of whom survived the procedure. This emboldened Boylston to inoculate many more.

Ultimately, Boylston and Mather claimed that their experiment proved the efficacy of variolation—that is, that the case fatality rate among their inoculated subjects was considerably lower than that of the uninoculated population that contracted the illness. Records from the time indicate that of Boston’s 10,600 residents, 5,889 people contracted smallpox and 844 died between April 1821 and February 1722, when the final cases were reported. These numbers suggest a case fatality rate of 14.33 percent. Boylston claimed the case fatality rate among his inoculated subjects was around 2 percent.

Cotton Mather’s enthusiasm for smallpox inoculation was perfectly understandable. The experience of losing his wife and three children to measles a few years earlier must have brought him to the brink of despair, reminded him of Job, and tested his deep religious faith. Why would a loving God allow him—a lifelong devoted servant—to suffer such a grievous loss? Mather wondered if it was punishment for sins he’d committed in his past, and he probably contemplated the possibility he had erred in his judgement of the Salem Witch Trials. Under these circumstances, it’s easy to understand why he perceived inoculation to be a gift from God and tool of redemption.

The trouble was that—under the influence of such thoughts and feelings—Mather and Dr. Boylston probably lost their unbiased posture in evaluating the safety and efficacy of inoculation. After performing the procedure just a few times without killing the patients, they seem to have placed great faith in it. It’s possible the procedure worked as intended on some if its subjects. The difficulty in evaluating its safety and efficacy lies in the large number unknown and unquantified factors with which Mather and Boylston contended, starting with the procedure’s crudeness. Dipping a dirty needle into a sick person’s smallpox pustule and then using the needle to perforate a healthy person’s skin provided no means of controlling the purity and quantity of the inoculum.

Within greater Boston, the total number of infected may have been underreported because many suffered only minor symptoms and did not seek medical care. There is also the possibility that Boylston overstated the number of people he inoculated. The Harvard library literature on the controversy states it was around 180. Subtracting the six who died after inoculation leaves 174. The uninoculated case fatality rate of 14.33 percent suggests that around 149 of these subjects would have survived the infection anyway, which suggests that inoculation protected about twenty-five from death.

One also wonders if Boylston’s inoculated subjects were, overall, in better health than many of those who died of smallpox during the outbreak. He claimed his subjects were “of all ages and constitutions,” but the precision and reliability of this assertion is questionable. It’s likely the Harvard students and faculty were some of the healthiest and best nourished in the greater Boston area. On the other hand, the nutrition, possible co-morbidities, and housing quality of all those who purportedly died of smallpox between October 1721 (the outbreak’s deadliest month) and March 1722 were not precisely documented. Smallpox hit poor families the hardest. They were often malnourished, with multiple family members living in cramped, poorly ventilated quarters and sharing the same bed with rarely washed linens—an unwholesome situation that was exacerbated during Boston’s long and severe winters.

Dr. William Douglass, who happened to be the only university-trained (Edinburgh) medical doctor in Boston, was sharply critical of Reverend Mather and Dr. Boylston. In his essays—published in the The New England Courant—he asserted that the inoculation procedure was potentially fatal and that it was likely spreading the disease, especially considering that Boylston and Mather were not placing their inoculated subjects in a regulated quarantine. The publisher of the Courant, James Franklin, entirely agreed with Dr. Douglass’s view of the matter. James’s sixteen- year-old brother, Benjamin Franklin, was the editor, and he probably had a hand in fashioning Douglass’s satirical style.

A passionate debate ensued in Boston’s pamphlets, newspapers and pulpits, with Dr. Douglass criticizing Dr. Boylston as an ignorant practitioner with no more skill than “a cutter of stone,” a double reference to a quarry laborer and to Hippocrates’s proscription to physicians not to “cut for stone”—that is, to operate for kidney stones, which would likely cause more harm than good. He marveled that Boylston could “infect a family in town in the morning and pray to God in the evening that the distemper may not spread.” Cotton Mather and his influential father shot back that inoculation was “a wonderful providence of God.”

Increase Mather wrote a pamphlet on the controversy in which he proposed that getting inoculated was a religious obligation and that Dr. Douglass would likely be pilloried in his native Scotland for defying this obligation. This triggered a response from another prominent clergymen, Reverend John Williams, who asserted that father and son Mather were violating the “Rules of Natural Physick” and making dangerous arguments based on the procedure’s African roots, of which they knew little. Others in Boston who remembered the role played by father and son Mather in the Salem Witch Trials suggested that it was they after all who were practicing witchcraft. Cotton Mather replied that he was not arguing on religious or metaphysical grounds, but from pure empiricism. “Of what Significancy, are most of our Speculations?” he asked. “EXPERIENCE! EXPERIENCE! ‘tis to THEE that the Matter must be referr’d after All.”

Despite stiff opposition, intimidation, and even death threats, Mather and Boylston prevailed in promoting inoculation in the colonies. Two years after the Boston outbreak, Boylston traveled to London, where he published an account of his experiment titled Historical Account of the Small-Pox Inoculated in New England. James Jurin, the Secretary of the Royal Society, was sympathetic to Boylston’s argument, which he concluded was consistent with survey data he solicited from inoculation proponents in England during the same period. Boylston was made a member of the Society in 1726.

The red-hot public debate in Boston over smallpox inoculation in 1721–22 resembled the debate over COVID-19 vaccination in 2021–22. Proponents back then asserted they had obtained enough evidence of the procedure’s safety and efficacy to warrant inoculating the entire population. Detractors argued it was a novel and unproven procedure that could do more harm than good. In 2021, proponents of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines proclaimed they were safe and effective, while critics argued the novel genetic technology had not been sufficiently tested over a sufficiently long period to warrant using it on the entire population, especially on the young and healthy for whom COVID-19 posed little risk.

Both debates recall Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.’s remark that “science is the topography of ignorance.” There is a great deal we don’t know about why smallpox affected early 18th-century populations in the way it was perceived and recorded at the time. Likewise, the passionate proponents of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines made all manner of efficacy and safety claims that have not been confirmed by humanity’s subsequent experience with these products.

We often make the unexamined assumption that “medical science” is akin to Newtonian mechanics, but this is a gross misconception. The causes of sickness and health—both in individuals and in large populations—are immeasurably more complex and multifactorial than most other objects of scientific analysis. Consider that while many reasonable people often debate about health and disease, none would debate about whether jumping off twenty-story building onto concrete would result in severe injury or death. A complex situation is inevitably riddled with ambiguity and uncertain outcomes and therefore becomes a subject of opposing interpretations and debate.

The human mind also tends to be very uncomfortable with complexity and ambiguity and therefore seeks schemes and tools for cutting through it. When an apparent solution presents itself—especially if the solution offers the promise of substantial personal gain—the observer may become very biased in his evaluation of it.

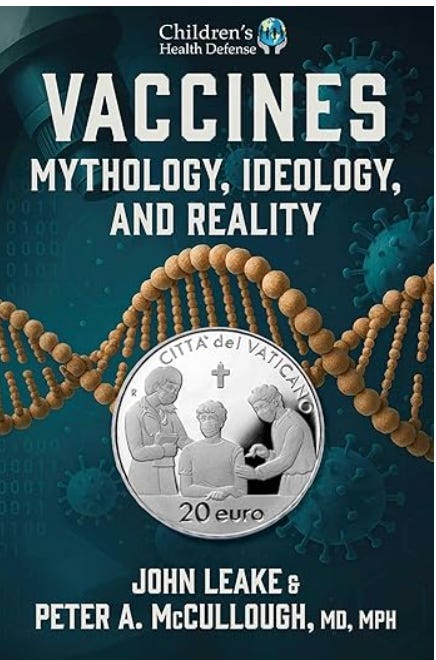

From: Vaccines: Mythology, Ideology, Reality, by John Leake and Peter A. McCullough, MD, MPH, SKYHORSE /Childrens Health Defense Books, July 29, 2025.

Please click on the image below to order your copy.

Vaccines: Mythology, Ideology and Reality is on my list of books to read. It is very necessary to read a number of books on a subject in order to gain knowledge. Another book, which sounded very interesting was Gavin de Becker's Forbidden Facts. I already have a number of other books in my library on the subject of vaccines, which are also enlightening. The first book I bought on the subject was back in the 1980s, Ida Honoroff's Vaccination the Silent Killer.

We can't even get a rational or plausible explanation for how we built hundreds or more ornate architectural masterpieces in the 1800s without a power tool, never mind cranes, trucks, and roads. Including around 80, yes, 80 mansion-like insane asylums in the second half of the century, concurrent with the orphan trains operation, and the civil war. Or was it really a war on civilians?

Why would we believe the tale of the witch trials? We should be more focused on determining the fable's motive. The smart money's on to make Christians look bad.