The 1952 Polio Scare and 1955 Vaccine

Reviewing America's first public health scare and mass vaccination campaign in the age of mass media.

Readers often ask how the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccine rollout of 2020-2021 compares with the great polio scare of the early 1950s and the vaccine rollout of 1955. This is an endlessly fascinating subject that we cover extensively in our forthcoming book, Vaccines: Mythology, Ideology, and Reality.

The question of how the vaccine response to COVID-19 compares to the vaccine response to Polio often comes up in discussions among policymakers on Capitol Hill.

I expect it may come up in tomorrow Senate (Homeland Security and Government Affairs Committee) hearing titled The Corruption of Science and Federal Health Agencies: How Health Officials Downplayed and Hid Myocarditis and Other Adverse Events Associated with the COVID-19 Vaccines.

The first thing to bear in mind about Poliomyelitis is that its causative agent—Poliovirus—is generally thought to have been endemic to all human populations since ancient times. By endemic, I mean that it had consistently been present among humans for centuries.

According to the CDC, about 70 percent of people infected with poliovirus experience no symptoms, while about 25 percent experience mild or flu-like symptoms that may be mistaken for many other illnesses. Less than 1 percent of infections result in mild to severe paralysis.

That Polio had long been endemic makes it starkly different from SARS-CoV-2—the causative agent of COVID-19—which was created in a lab sometimes between the years 2015-2019. Because SARS-CoV-2 was a novel virus, most of humanity in 2020 was immunologically naive to it, though a small percentage of humanity may have possessed some immunity from earlier exposure to SARS-CoV-1, which apparently emerged in China in 2002-2003 (though it too may have originated in a lab).

According to conventional history, the first likely modern medical reference to polio was in the 1789 A Treatise on Diseases of Children by the English physician Michael Underwood, who described it as a “debility of the lower extremities in children.” The book makes no reference to outbreaks of the disease.

The first detailed clinical description was written by the German orthopedic doctor, Jakob Heine, in 1840.

In 1909, the Austrian physicians Karl Landsteiner and Erwin Popper hypothesized that polio may be caused by a “virus” in the modern sense of the word—that is, a submicroscopic infectious agent.

With increasing urbanization in Europe and America between 1650-1950, it’s likely that most people were exposed to the poliovirus during infancy and early childhood, but the medical literature records no remarkable clusters of paralytic polio before 1894, when an outbreak in Vermont was documented.

The disease only became a serious public health problem at the beginning of the 20th century, when communities in the United States experienced what may be characterized as epidemic outbreaks of paralytic polio, especially during the summer months.

This was likely an unforeseen consequence of hygiene and sanitation improvements at the turn of the 20th century, which resulted in larger numbers of infants ceasing to encounter the pathogen during their early childhood years, between the ages of six months and five years, when the infection is typically very mild and confined to the throat and GI tract.

Likewise, and increasing number of girls did not encounter the pathogen before they began bearing children, and therefore did not pass maternal immunity to their nursing infants, thereby protecting them during the first six months of life.

The lack of exposure to polio at a young age was apparently more common among the affluent, making them more vulnerable to severe disease later in life. A notable patrician who was thought to have been struck by paralytic polio—at the age of thirty-nine—was Franklin Delano Roosevelt in the summer of 1921. Roosevelt’s paralysis and struggle to recover ultimately came to be known by the public as a notorious case of polio, though the diagnosis was never laboratory confirmed, and it’s possible he was struck by another illness such as Guillain-Barré syndrome.

What appeared to be an increasing incidence of paralytic polio after 1925 coincided with the development of institutional mechanisms for public health surveillance and reporting in all states. The first US national health survey was conducted in 1935. During the 1930s there was a growing fear of polio. That it seemed to most often strike the children of the affluent made it a prime candidate for vaccine development.

in 1948, a Public Health Survey revised morbidity reporting procedures, at which point the National Office of Vital Statistics took charge of this procedure.

In 1949, a research group headed by John Enders at the Children’s Hospital in Boston published that it had cultivated poliovirus in human embryonic tissue in a lab. This was heralded as a major facilitator of vaccine research. Also in 1949, the National Office of Vital Statistics began publishing weekly Public Health Reports. In 1952, mortality data were added to the publication.

By then, the U.S. population had grown to 153 million. Most households had a radio and about 32 percent had a television. All the elements were in place for America’s first public health scare facilitated by national reporting and rapid dissemination through mass media.

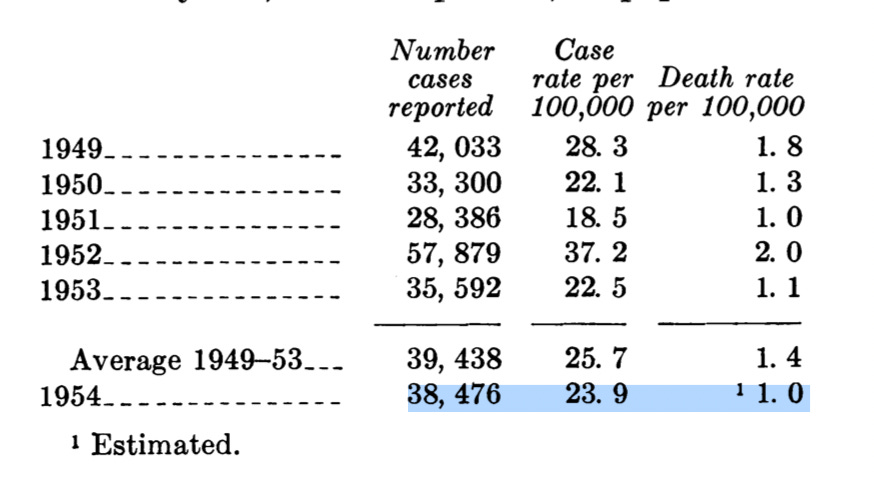

That summer the nation was gripped by polio fear. The reported incidence of the disease had been rising in recent years, but in 1952, nearly 58,000 cases were reported with 3,145 people dying and 21,269 left with mild to disabling paralysis.

This proved to be the worst year during the period of nationwide reporting before the introduction of polio vaccination in 1955, as the following table shows.

Here it should be noted that, with the entire medical profession on high alert for polio throughout the 1940s and early ’50s, it’s likely the disease was frequently over-diagnosed. As Humphries and Bystrianyk point out in their book Dissolving Illusions:

In 1955, the year the Salk vaccine was released, the diagnostic criteria became much more stringent. If there was no residual paralysis 60 days after onset, the disease was not considered to be paralytic polio. This change made a huge difference in the documented prevalence of paralytic polio because most people who experienced paralysis recovered prior to 60 days.

Uncertainty about diagnosis prior to lab testing in 1958 touches on the biography of Republican Senator Mitch McConnell. In 2021, McConnell urged Americans to get COVID-19 vaccines, and he mentioned his diagnosis with polio in 1944 when he was two years old. On February 13, 2025, he was the only Republican Senator to vote against Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s confirmation as HHS Secretary. His proffered reason was that his childhood experience with polio made him appreciate the “miracle” of vaccines, which, as he saw it, Kennedy was questioning.

Did Senator McConnell really have paralytic poliomyelitis when he as two years old? A public health report titled “Incidence of Poliomyelitis in the United States in 1944” reported an above-average national incidence of polio that year, with a total of 19,053 cases. However, no outbreak in Alabama was noted, and the American South experienced no major outbreaks until the late 1940s. As McConnell described his case in his memoir: “The disease struck and weakened my left leg, the worst of it my quadriceps.” Given that he was two years old at the time—when the disease is usually very mild—and given that it was apparently an isolated case in Alabama that year, one wonders if perhaps the leg weakness he experienced in his left quadriceps might have been caused by a different affliction. Maybe it was caused by polio, but the doctor in Five Points, Alabama had no laboratory means of confirming it. At any rate, the weakness in the toddler’s left leg resolved two years later. In 1967, McConnell was deemed unfit for military service not because of leg weakness, but because of optic neuritis.

While 21,269 people with mild to disabling paralysis is a lot, it was a tiny fraction of the total U.S. population of 153 million—that is, 14 in 100,000. Nevertheless, with constant radio and television reporting about children being paralyzed and placed in iron lungs, many Americans reported being more frightened of polio than of any other danger, including atomic war. It was a conspicuous example of how mass media can focus attention on a particular threat, causing widespread loss of perspective. As a 2005 report in the Yale Medicine Magazine put it,

In truth, polio was never the raging epidemic portrayed by the media, not even at its height in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Ten times as many children would be killed in accidents in these years, and three times as many would die of cancer.

The nation experienced a similar loss of perspective in 2020, with the daily barrage of media reporting on case counts and purported hospitalizations with COVID-19. In 2020, Dr. Anthony Fauci was portrayed by the mainstream media as a savior who would, in his position as director of the NIAID, supervise the rapid development of a COVID-19 vaccine.

In 1952, Jonas Salk seemed like the most likely savior. The reader will recall that, seven years earlier, while working with Dr. Thomas Francis at the University of Michigan, he had developed the first inactivated influenza vaccine for the U.S. War Department. Salk again expressed high conviction that an inactivated vaccine—that is, one composed of a killed poliovirus—could induce immunity without risk of infecting the patient. With funding from the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis—now known as the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation—he got to work on his polio vaccine.

Instead of using human tissues for growing poliovirus, Salk used minced rhesus macaque monkey kidneys, which were highly efficient at growing poliovirus. During the developmental period of creating the Salk (and later the Sabin) vaccines, approximately 100,000 monkeys were killed and their kidneys harvested. After growing the poliovirus in monkey kidneys, it was then killed or “inactivated” with formaldehyde.

On March 26, 1953, Salk went on CBS radio to report a successful test on a small group of adults and children. His announcement created mounting excitement and hope, and the following year mass trials involving over 1.3 million children (aged 7-8) were conducted.

Here it is important to note that the children who received the experimental vaccine were not challenged with inoculations of live poliovirus in the way that Salk had challenged mental health patients with influenza virus in 1943.

Following revelations of Nazi medical experimentation during the Nuremberg Trials, such experiments without informed consent were prohibited. While the ethical reasoning is sound, the lack of challenge experiments in the modern vaccine era has always made it difficult to evaluate the efficacy of vaccines.

Instead of being challenged, the children in the Salk field trial then returned to their normal lives and were observed to see if they developed symptoms of paralytic polio.

It’s likely that most of the children who received the shot had already been exposed to polio during their first six years of life and were already immune. Moreover, the fact that 70 percent of people who contract the poliovirus experience no symptoms meant that much of the vaccinated group would never develop and report symptoms of polio even if the vaccine wasn’t effective.

Dr. Thomas Francis, Jr. was tasked by the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis to conduct an independent evaluation of the field trial results. While Francis was undoubtedly a gifted virologist, he was hardly an impartial evaluator, as he had long been Jonas Salk’s teacher, mentor, and senior research partner.

Today, most accounts of Salk’s vaccine field trial characterize it as a clear and resounding success, but the eminent virologist John Enders—who won the Nobel Prize in 1954 for his technique of cultivating poliovirus in human embryonic tissue—expressed concern about the safety and efficacy of Salk’s inactivated vaccine.

In a paper that Enders published in 1954, he questioned the safety of a vaccine prepared from virulent poliovirus, whatever “inactivation” method was used. He described Salk’s work as “most encouraging” but cautioned that “the ideal immunizing agent against any virus infection should consist of a living agent exhibiting a degree of virulence so low that it may be inoculated without risk.”

To make matters even dicier, already in 1954, researchers had observed that rhesus monkey kidneys were contaminated with simian viruses that could cause other diseases including cancer. Nevertheless, tremendous excitement grew with reports that the field trial data was being compiled and analyzed.

On April 12, 1955, exactly ten years to the day after the death President Roosevelt, a scheduled press conference consisting of 150 newspaper, radio, and television reporters assembled at an auditorium at the University of Michigan. Sixteen television and newsreel cameras were assembled to broadcast the event, while 54,000 physicians assembled in movie theaters across the country to watch the closed-circuit television broadcast of the event. Eli Lilly paid $250,000 for the broadcast. All over the country, Americans tuned in on their televisions and radios. Department stores set up loudspeakers for their customers to hear the conference.

The player who stepped onto the stage of this extraordinary mass media theater was not Jonas Salk, but his senior partner Thomas Francis Jr. He approached the podium and announced that the vaccine had proven to be safe, effective, and potent.

Jubilation erupted. In the auditorium and across the country, people embraced and wept tears of joy. Church bells range and congregations offered prayers of thanks. Factories paused production so that the workers could think in silence on their great benefaction. Shopkeepers put signs in their windows thanking Dr. Salk. To many Americans, the announcement of the effective vaccine recalled the news reports a decade earlier of the German and Japanese surrenders at the end of World War II.

The fanfare did not last long; 200,000 children in five Western and Midwestern USA states soon received a polio vaccine containing live virus because the manufacturer had employed a defective method for inactivating it. Reports of paralysis soon followed, and within a month the first mass vaccination program against polio was abandoned.

A subsequent investigation discovered that the vaccine, manufactured by Cutter Laboratories in California, had caused 40,000 cases of polio, leaving 200 children with varying degrees of paralysis and killing ten. The Cutter incident was a contributing factor in the decision to replace Salk's formaldehyde-inactivated vaccine with Albert Sabin's attenuated polio vaccine. Sabin's vaccine offered the advantage of oral administration and seemed to confer more robust immunity, but it could also reverse its attenuation after passing through the gut, thereby causing occasional cases of paralytic polio until the 1990s, when a modified Salk vaccine was re-introduced.

In 1961, Simian Virus 40 (SV 40)—a monkey virus suspected of causing cancer in humans—was discovered to have contaminated the Salk and Sabin polio vaccines. Initial steps to remove the contaminant were inadequate and SV-40 continued to contaminate the inactivated and live-attenuated vaccines through 1963.

The multiple safety failures that beset the rollout of polio vaccines demonstrated the hazards of hastily administering a new immunological product to millions of people.

The extreme difficulty of getting a new vaccine right in its first and even second iteration teaches us that great caution is warranted when rolling out a new one. This lesson was totally flouted during the COVID-19 pandemic.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: If you found this essay interesting, please consider pre-ordering a copy of our forthcoming book, Vaccines: Mythology, Ideology, and Reality, which is being published by the SKYHORSE Children’s Health Defense imprint on August 5, 2025. Please click on the cover image below to pre-order your copy.

POSTSCRIPT: After I posted the original essay, multiple readers commented that the essay is not a complete exposition of poliomyelitis and other possible causes of lameness in the lower extremities. To be sure, one could dedicate an entire, large book to this subject. My brief essay today was not intended to be a complete explication of the subject.

For the purposes of this postscript, I would like state that I am familiar with the theory that what was frequently diagnosed as polio was caused by exposure to lead arsenate pesticide, which was heavily applied to trees in New England following the gypsy moth infestation that began in 1869, and by the enormous use of DDT in the 1940s and ‘50s.

We address this theory in our book chapter on polio, but we do not believe that pesticide toxicity in the United States is sufficient to nullify all the field and laboratory observations, conducted by medical researchers in multiple countries between Jakob Heine’s paper in 1840 and John Enders’s paper in 1949.

Landsteiner and Popper’s 1909 paper,”Uebertragung der Poliomyelitus auf Affen”(Transmission of Acute Poliomyelitis to Monkeys) presents a persuasive argument that whatever causes the conspicuous damage to the gray matter of the spine is not a bacteria.

When the diseased spinal material—taken postmortem from a boy who apparently died of poliomyelitis near Vienna—was injected into rabbits, guinea pigs, and mice, it caused no disease. However, when this same material was injected into monkeys, it caused the same clinical symptoms and spinal cord damage that appeared in humans. I believe that Landsteiner and Popper were serious researchers who were acting in good faith, and that the cases they studied were not children who’d been exposed to lead arsenate or DDT.

I was 13 in 1955. I did not get the vaccine or take the oral version later. I did not get polio. I did not take the covid shots. I did get the omicron version when I went on a trip in 2022. It was like a 6 day cold with one variation. I did not want to eat anything for a day. Otherwise, it was very much like the colds I've had over my lifetime. So, here I am a useless eater still alive at 83.

I have been taught the story of the polio vaccine fiasco(s) as a student in UCSF School of Pharmacy ( 1990 plus/minus) and was shocked during the COVID vaccine launch at the number of “highly educated” people who only believed the simplistic propoganda about its great success. The true history summarized above is the best I’ve ever seen.