Why U.S. Interventionism Fails

Reflections on the fall of Saigon fifty years ago.

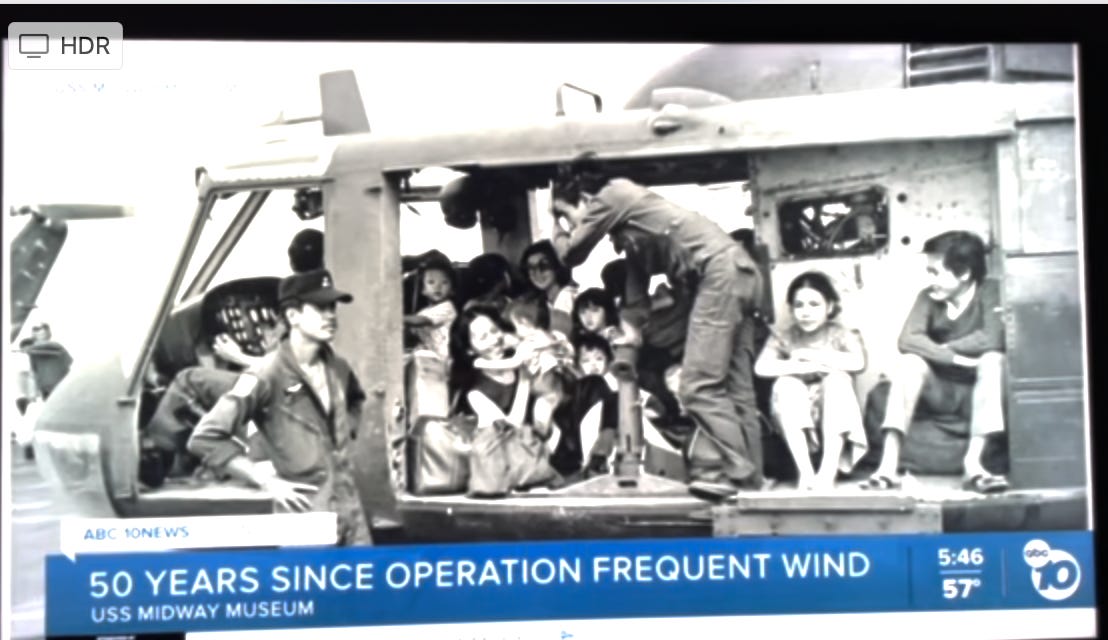

My sister-in-law was born in Saigon just six days before it fell to the North Vietnamese Army on April 30, 1975. Together with her mother and siblings, she was one of thousands of South Vietnamese who were evacuated by helicopter in the U.S. military’s Operation Frequent Wind.

A few days ago, on April 30, her family attended a 50th anniversary ceremony on board to the U.S.S. Midway in San Diego to commemorate the evacuation. Local news stations captured footage of her and her siblings at the ceremony and featured a photograph of them on that fateful day fifty years ago right after they landed on the deck of the Midway.

Most of the men in my sister-in-law’s family—including her father—fought hard against the communist army of North Vietnam. However, despite their efforts—and the massive support of the U.S. military—they were unable to prevail. Why?

The most plausible explanation is that the government of the Republic of Vietnam was unable to counter the communist message that the Americans were, like the French before them, imperialists who didn’t really care about ordinary Vietnamese people, but wanted to exploit the resources of their beautiful and fertile country. In other words, the U.S. government had a credibility problem.

Intervening in the affairs of others—including those of the adult members of your own family—is always an extremely difficult undertaking. There are many reasons for this, starting with the fact that anyone who wishes to intervene rarely if ever knows precisely what is going on in the others’ affairs. Indeed, many people don’t fully know what is going on in their own marriages and families.

Thus, trying to intervene in the affairs of people who live in a foreign country 9,000 miles away—people about whom you know nothing and with whom you cannot even speak—is a formidably difficult undertaking.

This obvious fact hasn’t deterred Washington’s foreign policy gang from attempting to do this again and again since they lost their bid in South Vietnam fifty years ago.

Young American men who reached adulthood in the sixties were not animated with the desire to die defending South Vietnam.

Dick Cheney frankly expressed this in a 1989 Washington Post interview when he stated: "I had other priorities in the '60s than military service."

The natural tendency to have “other priorities” than getting shot in foreign lands is why the current U.S. government has found it expedient to arm Ukrainian men and encourage them to get shot instead of sending American soldiers into the fray.

It seems to me that anyone who has studied history could have known in 2022 that the U.S. government’s proxy war in Ukraine was doomed to fail, just as its wars in Vietnam and Iraq failed. This raises the suspicion that waging war is the primary objective, and not winning it. As Orwell wrote about the state’s war in Eurasia in 1984:

The war is not meant to be won, it is meant to be continuous. … The war is waged by the ruling group against its own subjects and its object is not the victory over either Eurasia or East Asia, but to keep the very structure of society intact.

Orwell nailed it, no question. There is a telling theme with the US selection of places to hold our continuous wars. I. F. Stone said it so concisely: "You can't win a war in a peasant country fighting on the side of the landlords." The wars were chosen to be lost.

I wrote a letter to President Nixon in 1971, telling him I didn't want to die in Vietnam. I told him I might be a coward. I was 11.